It may surprise some, but my interest in cognitive sciences was initiated by the bullshiters I frequently encountered in seminars, meetings and other events related to my business sector (entrepreneurship, creativity and computer science). I was bombarded with countless theories and concepts, and more importantly organisational ones, each one more ingenious than the other and which seemed able to solve anything. All these theories were of course backed up by so called “scientific” articles. Despite this evidence seen as irrefutable by their authors, I was wary of this “silver bullet” that was regularly marketed to me, sometimes advertised simply as such. In fact, some of these poorly argued theories sparked my interest more than others. On the one hand, some of the proposed arguments annoyed me by being inappropriate, and on the other, I felt that some theories were more credible than others, but poorly addressed or interpreted. Of course, at the time, I was not aware that my own reasoning based on my intuition was not appropriate, but I still felt that there was something to be done in this area, without really knowing what. A common trait in all these “stories” was that the “evangelists” (a regularly used term) of these methods seldom seemed to really master their subject, in my opinion. All that seemed important to them was to sell their ideas at any cost, including bulling, i.e. not actually lying, but using enumerations in keeping with the theory, to better convince their audience (Perry, 1963). Using reference philosophical texts on the epistemology of cognitive sciences, I will try to make the connection with the methods used in the Lean Startup, still very popular today, and try to explain the risks of such an approach.

Already in 1904, the geologist Thomas C. Chamberlin approached the topic of methodology in scientific research, in his article “The Methods of the Earth-sciences” (Chamberlin, 1904). According to him, the best method to verify a hypothesis is the one that is most precise, but also exhaustive and unbiased. To avoid this last risk, the researcher (or entrepreneur looking for a business model) must make his or her observations without any preconceptions. Without development, this approach is problematic as it prevents the researcher from detailing an observation to obtain relevant data. As Karl Popper (1969) demonstrated to his students, the simple instruction “observe” naturally leads to the following questioning: “What should be observed?” The choice of our subject of interest therefore arises from a starting hypothesis which arose from one or more observations. Moreover, a lot of our knowledge is built using the hypothetico-deductive model, as described by Bacon (1268). This procedure consists of first formulating a hypothesis, deducting its consequences and then testing them using experiments. Chamberlin (1904) proposed in opposition to “The Method of Colourless Observation” which has just been described, two other methods called “The Method of the Ruling Theory” and “The Method of the Working Hypothesis“. The first consists of carrying out as many experiments as needed to verify a first hypothesis. The second is to consider a hypothesis as tentative until observations contradict it. This is the method recommended in the business startup stimulation programs (including those in which I actively participate).

According to Chamberlin, this latter method can often degenerate into the first one if the experimenter is not vigilant. In both cases, a theory can be compared to the researcher’s child. It is easy to imagine how some people persist, like a magistrate who examines exculpatory and not always incriminatory evidence, a prisoner of his own beliefs and convictions, and only retains information that confirms his hypothesis, neglecting everything else. Because elaborating a theory based on a series of empirical observations, however numerous, confirming the underlying hypothesis, is not without a whole series of difficulties, including the problem of induction (Popper, 1969). Induction consists of a mental operation through which we go from given observations to a proposal that explains it. This method is therefore probabilistic since it is based on the principle that the greater the number of observations, the greater the likelihood that the general theory deduced from the latter be true.

However, according to Karl Popper (1969), no general theory can be justified using this method since most of the time it’s impossible to observe all instances of a type of observable facts since induction can only be justified by induction, which causes an infinite regress. Popper did not hesitate to characterize the generation of hypothesis by induction a myth in the development of objective scientific knowledge. His first argument concerns the selective nature of the observation. To observe, attention must be focused on a point of interest. This point of interest originates from a hypothesis that has been constructed from one or more observations. Which makes it a recursive process. This tendency to look for regularities in the world around us is a very powerful learning mechanism on which conditional reasoning is based. It seems natural, but can pose a whole new series of problems…

This method concerns multiple cognitive biases, of which the best known is the “confirmation bias“, the powerful effects of which have been demonstrated by Wason & Johnson-Laird (1972). Wason’s original experience (1960) suggested that participants discover a rule from the sequence of starting digits “2-4-6”. Participants could propose sequences of figures to test their hypotheses. They were then told whether this suite was compatible with the rule to be discovered. After making several proposals, they were then asked to formulate a general rule, of which they were absolutely certain. A positive or negative feedback followed. This task uses our ability to generate hypotheses but also the ability to give up. According to the author, these two processes would interact. The experiment was created to highlight the method most commonly used by the participants to find the rule. It also highlights the fact that most of the participants are prepared to formulate a rule based solely on proposals that correspond to their initial hypothesis. Most subjects proposed the sequence of numbers “4 – 6 – 8” (valid), then “6 – 8 – 10” (also valid) to prematurely announce the rule “two is added to each next digit“. In fact, the rule is “figures in ascending order” and only barely 21% of the participants found it without having an erroneous solution. More surprisingly, more than 51% of the proposals, with an erroneous solution, remained consistent with the latter. Most people, even if very intelligent, seem incapable of considering that there may be a different or more basic rule than the one that seems to work (Miller, 1967). Where most participants used the strategy to verify their hypothesis, the others tended to invalidate it using proposals such as “2 – 4 – 10” (valid) or “10 – 6 – 4” (invalid) or “1 – 7 – 13” (valid). As Popper (1969) stated, there is no “valid” inductive method since it is impossible to guarantee that a generalization from observations confirming a hypothesis, be correct.

A second major problem appears with the “always correct” theories that nothing seems able to dispute. These theories are often referred to as pseudoscience, due to this characteristic and one of the most commonly used examples to illustrate it in scientific psychology is psychoanalysis. Thanks to concepts such as ambivalence, resistance, repression or denial, it is always possible to interpret a behaviour with hindsight. A set of behaviours can therefore go in one direction or in the opposite direction without ever questioning the theory. It is these peculiarities that make psychoanalytic theories difficult to experimentally test, giving them longevity (in the case of French speaking countries) and the high progressiveness in their decline contrary to scientific theories that disappear abruptly when they are proven to be false backed up by new data (Meehl, 1978). For Popper (1969), a theory is only scientific if it is falsifiable. This falsifiability would be the demarcation criterion between a scientific theory and one that would not be. The latter formalised, at the end of the 1920s, his conclusions as follows (slightly adapted by myself):

- It is easy to obtain confirmations, or verifications for almost every theory, if confirmation is being looked for.

- Confirmations should only be considered if they are the result of risky predictions; that is to say, we should have expected an event which was incompatible with the theory and that would have refuted it.

- Every “good” scientific theory is a prohibition: it forbids certain things to happen. The more a theory forbids, the better it is.

- A theory which is not refutable by any conceivable event is non-scientific. Irrefutability is not a virtue of a theory (as people often think), but a vice.

- Every genuine test of a theory is an attempt to falsify or refute it. Testability is falsifiability; but there are degrees of testability; some theories are more testable, more prone to refutation, than others; they take as it were, greater risks.

- Evidence confirming the theory should not count except when it is the result of a genuine test attempt; which means that it can be presented as a serious but unsuccessful attempt to falsify the theory. (I speak in such cases of “corroborating evidence“.)

- Some genuine testable theories, when found to be false, are always upheld by their admirers, for example by introducing ad hoc an auxiliary hypothesis or by re-interpreting the theory in such a way that it escapes the refutation. Such a procedure is always possible, but it rescues the theory from being refuted at the cost of destroying, or at least lowering its scientific status. (I later describe such a rescue operation as a “conventionalist twist“).

Consequently, to increase the quality of a theory, it is necessary, not to increase the number of empirical observations that confirm it, but to actively seek events that make it impossible, such as the alibi of an alleged killer who prevents him from being physically at the scene of the crime at the time it occurred. Researchers (of a business model) must therefore formulate their theory by making clear how it can be refuted, and not the means by which it can be confirmed. Chamberlin (1904) proposed to use the method that he called “The Method of Multiple Working Hypothesis” which implies the elaboration, even before experimentation has begun, of multiple hypotheses, some of which contradict themselves. So, the researcher must have an open mind and remain open to all possible interpretations of a studied phenomenon, including the possibility that none of the explanations are correct, and that even some new explanations may appear.

This latter effect, more than desirable, is also compatible with the social sciences (in entrepreneurship), which often suggests that behaviour originates from multiple causes that can interact with each other and thus make the repetition and use of statistical tests complicated. This is the major problem in cognitive science. Meehl (1978) does not hesitate to declare that, according to him, the field of research in psychology (clinical, social, etc.) based on correlations and tests of variance is so problematic, that it is scientifically irrelevant. In his original article, Meehl detailed the 20 reasons that led him to declare that Popper’s method (1969) was incompatible with statistical tests such as variance testing and analysis. He declared no more, no less that “The almost universal dependence of the rejection of the null hypothesis is a terrible mistake, is fundamentally unhealthy, is a bad scientific strategy, and is one of the worst things that ever happened in the history of psychology“. To illustrate his point, Meehl states that the variability of psychological processes is so highly dependent on context, that it is impossible to recognise an interesting and relevant meaning outside the experimental environment designed by the researcher. To draw up a list of these parasitic variables is as impossible as quantifying the precise effects on a given dependent variable, not to mention that the samples used are often far too small. He goes even further by questioning meta-analysis aimed at linking studies that study the same psychological construct and to draw a general conclusion on its validity. For Meehl, researchers in psychology who wish to highlight the explanation of a theoretical construct, should prefer consistency testing to significant statistical tests, i.e. use different means and not redundant estimations of a quantitative value for this construct. He concludes by declaring that it is the very nature of certain fields of study in psychology, such as social psychology or differential psychology, which are not compatible with the suggested method and are probably doomed to never have any major theory, scientifically speaking.

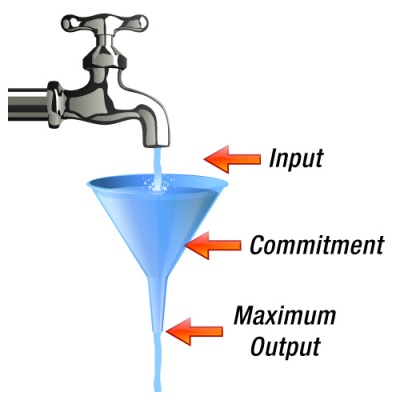

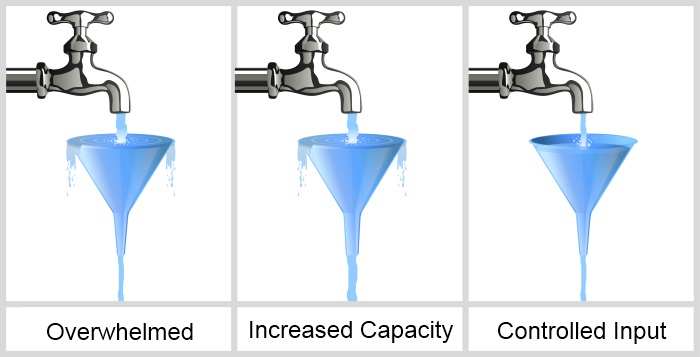

Considering everything mentioned previously, it should be noted that in social sciences (and therefore including entrepreneurship), many questions can be satisfied with dichotomous answers such as “Is this one better than the other?“. So, the question is not “what is scientific or not?“, or “what is the best method?“, but “what are the most appropriate tools to achieve this or that objective?” The entrepreneur’s is to use the appropriate tools for their research object and above all to correctly master them to avoid any erroneous interpretation of the results of their experiments, which could, in this precise case, lead to their loss with serious financial consequences. If the significance test was heavily abused in some areas of psychological sciences, to the detriment, for example, of the size of the effect test, is probably due to the way of funding research that drives the most brilliant theorists to publish or perish. The entrepreneur, very often put their own money, or their time, with no certainty of remuneration. Not addressing these issues seriously comes down to the same as putting all your eggs in one basket.

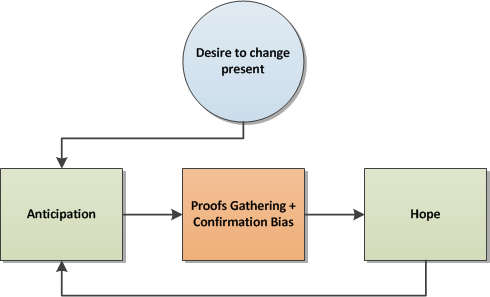

In conclusion, the entrepreneur (or professional researcher) must show intellectual honesty and be as rigorous as their role entails, even if in order to do so, they have to oppose the standards established by the markets (or institutions) in which they evolve. Paul E. Meehl (1989) said, in his famous courses on psychological philosophy the following: “If you get to a point where you say to yourself ‘I will cling to this blasted theory, whatever happens, come hell or high water’ you are no longer respecting the rules of scientific research”. The entrepreneur then enters the vicious circle of the optimistic entrepreneur where hope is fed by the information filtered through confirmation bias. And that’s exactly what you need to avoid at all costs.

References

Bacon, R. (1268). On Experimental Science.

Chamberlin, T. C. (1904). The methods of the earth-sciences. Popular Science Monthly, pp. 66:66-75.

Eccles, J. G. (1992). Under the Spell of the Synapse. In F. Worden, J. Swazey, & G. Adelman, The Neurosciences: Paths of Discovery, I (pp. 159-179). Boston: Birkhäuser Boston.

Meehl, P. E. (1978). Theoretical ricks and tabular asterisks: Sir Karl, Sir Ronald, and the slow progressof soft psychology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, pp. 46:806-34.

Meehl, P. E. (1989). Paul E. Meehl Philosophical Psychology Videos. Retrieved from Departement of Psychology of the University of Minnesota: http://www.psych.umn.edu/meehlvideos.php

Miller, G. A. (1967). The Psychology of Communication. New York: Basic Books.

Perry, W. G. (1963). Examsmanship and the Liberal Arts. In Examining in Harvard College: a collection of essays by members of the Harvard faculty (p. Examsmanship and the Liberal Arts.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Popper, K. (1969). Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. Routledge.

Wason, P. C. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12(3), 129-140. doi:10.1080/17470216008416717

Wason, P., & Johnson-Laird, P. (1972). Psychology of Reasoning: Structure and Content. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Recent Comments